In the era of colonial British rule over India, a direct link was sought to be created between the province of “Gurjara”, references to which are found in ancient inscriptions and texts, and the latter-day pastoral tribe of Gujjars. The colonial historians were not interested in the subject from the point of view of the Gujjars themselves but from the entire populace of western and northwestern India, which to them appeared to be radically different from the Indians living in the east and south. The Encyclopedia of Indo-Aryan Research gravely observed in 1912: “There are, moreover, special features of the structure and customs of Rajput and Jat and other northern communities in India which distinguish them from the Brahmanic masses of the interior, and may be attributed to difference of race, perpetuated by many generations of resistance to attacks from the outside.” This division of Indian people finds a strange echo in an official note from Prime Minister Winston Churchill to US President Roosevelt in 1942 on why a united India could not be granted independence: “The fighting people of India are from the northern provinces largely antagonistic to the Congress movement. The big population of the low-lying center and south have not the vigor to fight anybody.”

This fighting spirit was attributed to the alleged foreign origin of these northern communities, and the same cause was used to explain the rise of the Pratihara empire and its extension into the Gangetic plains from the west. The more enduring resistance of the Rajput clans in Rajasthan to the Islamic invaders was also attributed to their mythical Scythian ancestry, and as a convenient reason to explain why Rajputs were more “Brahmanical” than the other foreign descent communities. The Encyclopedia of Indo-Aryan Research states: “The contests with the Muslim invader of a few centuries later had the effect of consolidating the Rajput devotion to the scrupulous observance of Brahmanic injunctions as to marriage and intercourse with other castes which especially distinguished them from their foreign oppressors; and to the present day, they stand out from the rest of the community in the high value they attach to these matters.”

British civil servant and historian VA Smith, describes how this assumption was transformed into a hypothesis (similar to the Aryan Theory) in his 1914 book The early history of India: “In this place I desire to draw attention to the fact, long suspected and now established by good evidence, that the foreign immigrants into Rajputana and the upper Gangetic provinces were not utterly destroyed in the course of their wars with the native powers…and there is no doubt that the Parihars and many other famous Rajput clans of the north were developed out of the barbarian hordes which poured into India during the fifth and sixth centuries. The rank and file of the strangers became Gujars and other castes, ranking lower than the Rajputs in the scale of precedence.”

Thus the colonial approach to the study of the Gujjar tribe was subsumed to their already established belief that all the peoples in the western half of North India were of foreign descent. The problems of this approach for the wider population was explained in this post: Foreign tribes Indian clans which shows that there is no evidence for the movement of “hordes” of communities into India during that era, but rather campaigns of states established outside of India by those hordes. In the specific case of the Gujjars the British civil servant and amateur linguist GA Grierson wrote in 1916: “Gurjars, the ancestors of the present Gujars, probably entered India together with Hunas and other marauding tribes in about the sixth century AD and that some of their fighting men became recognized as Rajputs. As may be expected, Gujar herdsmen (as distinct from the fighting Gujars who became Rajputs) are found in greatest number in the North-West of India from the Indus to the Ganges.”

Dichotomies in linking Gurjara with Gujjar

- The ancient inscriptions and texts for Gurjara all refer to a territory covering southwest Rajasthan and northern Gujarat. But the pastoral Gujjars live outside this territory: the main population in Punjab and the adjoining sub-Himalayan belt, followed by western Uttar Pradesh, and then the eastern districts of Rajasthan taking the third spot in total numbers.

- The second dichotomy is that while these inscriptions refer to an orthodox Hindu kingdom, the main population of the Gujjars are either pastoral or agricultural.

These two dichotomies actually became the basis for the hypothesis by Smith, Grierson, Jackson, and Bhandarkar. A foreign tribe invaded and settled down in Punjab, but for some unexplained reasons, the warlike elements of this tribe separated and traveled further south into Rajasthan where they established a kingdom. The unwarlike elements remained behind and became the ancestors of the pastoral Gujjars. VA Smith was honest enough to admit that this was only a hypothesis and that he had made an astonishing assumption about the term Gurjara referring to a foreign tribe even though: “there is nothing to show what part of Asia they came from or to what race they belonged.” And then, of course, there is the problem of explaining how a tribe from a sparsely populated region outside India, wherever that may be, multiplied in numbers to stand out in an already densely populated, fertile land like India?

Normally a hypothesis is constructed on the basis of certain facts, but the colonial myth makers used their own hypothesis as a base for manufacturing a stupendous new hypothesis…that of a separation of warlike elements from the main tribe and their unexplained migration away from fertile lands and into the desert! Any foreign tribe would be competing for resources with the indigenous population, and purely from the view of self-preservation, they would more likely stick together than separate. And the only place where such a tribe would have the ability to establish a kingdom would be the place which the whole tribe inhabits. Flimsy as these multiple hypotheses are, they fall flat on their face under the weight of linguistic evidence:

- The third dichotomy: even though the Gujjars reside primarily outside Gujarat and southwestern Rajasthan, they speak a language which is a cognate of Rajasthani and Gujarati.

Just like Rajasthani and Gujarati, the Gujari language has its roots in Sanskrit and has developed from the later corruptions like Prakrit and Apabhramsa spoken in Rajasthan and Gujarat. But the colonial mythmakers were not to be deterred by minor things like data and evidence…they constructed yet another hypothesis. That Gujari was the pre-existing language of the foreign tribe, and it has given birth to the languages spoken in Rajasthan and Gujarat, rather than the other way round! On linguistic grounds, this hypothesis doesn’t stand because the use of Apabhramsa in literature can be dated to centuries before the term Gurjara emerged. But even if this flimsy hypothesis is accepted, the big question then arises: why did this foreign language not affect the languages of Punjab, where this alleged foreign tribe allegedly first entered and where the largest population lives? Linguistic data shows that Gujari shares characteristics of the languages in the Rajasthani and Gujarati group which became more pronounced between the 13th and 15th centuries. The Gujari language cannot be dated to a previous period, and certainly not back to the 6th century, for the simple reason that spoken languages cannot be unchanged for 1000 years.

- Lastly, there are several other communities that still bear the cognomen of Gurjara. These communities are strictly non-tribal and have no connections to the pastoral Gujjars.

Communities like the Gurjar Kshatriyas, Gurjar Vanias, Gurjar Jains, and Gurjar Oswals, all live in the state of Gujarat and speak the Gujarati language. The other distinctive feature for these communities is the smallness of their numbers in the population of Gujarat. The Gurjar Oswals trace their origin to the Rajasthani town of Osian, which we know was an important religious center under the Imperial Pratiharas as well as the Mandor Pratiharas, and which contains the earliest specimens of the Maru-Gurjara style of architecture. The Gurjar Jains and Gurjar Vanias are largely found in Kutch and claim a Rajasthani Rajput ancestry. The Gurjar Kshatriyas are mostly craftsmen and artisans who again trace their ancestry to Rajasthan, and claim to have originally been Rajputs. They too are located primarily in Kutch and Saurashtra. The ancient province of Gurjara was confined to northern Gujarat and southwest Rajasthan; it did not include the virtual island of Kutch or the peninsula of Saurashtra. That is why communities migrating from southwest Rajasthan into these latter regions would keep the cognomen of “Gurjara”.

The colonial historians manufactured yet another hypothesis to explain this last dichotomy: namely that these tiny communities bearing the cognomen Gurjara were probably part of the invading “horde” all following different professions like trade, craftsmanship, finance, etc! They couldn’t be bothered about providing any explanation to the obvious follow up to this fantastic new assumption: if these different communities were all part of the invading horde, why don’t we find them anywhere in places where the alleged horde allegedly settled in greatest numbers: namely Punjab and the northwest, J&K, western Uttar Pradesh, and east Rajasthan? Why are they all found only in Gujarat? The location and numbers of these communities all prove beyond any doubt that they take their name from Gurjara, which was the name of a province in ancient times.

[The case of the Gurjara Brahmans]

The colonial historians tied themselves up in knots in these frantic efforts to connect the Gurjara province with a foreign pastoral tribe, then the latter with the warlike Rajputs, and further to trace communities of traders and craftsmen. The crowning foolishness on top of these colonial myths was the unexplained geographical separation of this hodge-podge of communities. But there was another knot in this twisted tale. Some of them now claimed that just as a warlike segment of the invading horde became Pratihara Rajputs, that horde also had a priestly class, which became known as Gurjara Brahmans who are today found in Gujarat, Rajasthan, and Maharashtra. The obvious riposte to this assumption is the same as for the other Gujarat-based communities: If the Gurjara Brahmans are indeed “high priests” of the mythical gurjar race, why aren’t they found co-inhabiting the main settlements of that tribe in Punjab??

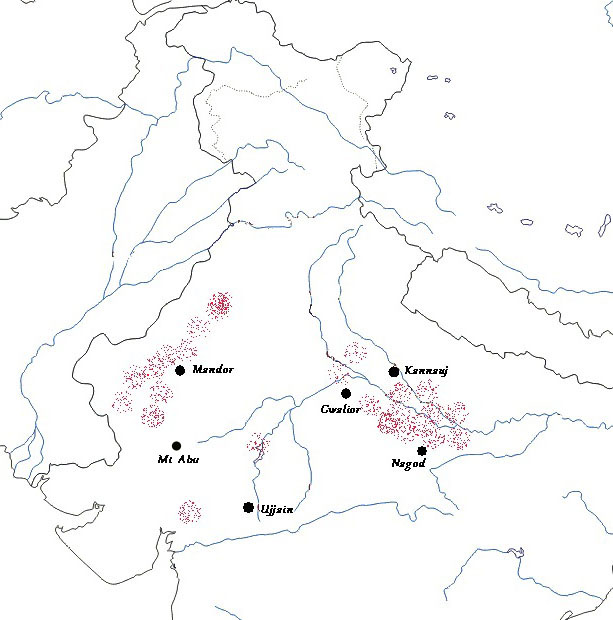

The biggest stumbling block for this convenient new hypothesis is that while Pratiharas were a clan of Rajputs, Gurjara Brahmans are not a clan…they’re not even a community of Brahmans. In fact, Gurjara Brahman is a geographical grouping of Brahman communities found in Gujarat and Rajasthan. As a word of explanation, Brahman communities in India are grouped geographically, into five North Indian provinces (hence called the Pancha Goud) and into five South Indian provinces (the Pancha Dravida). Intriguingly, while the Gurjara province was located in Western India, it is included in the Pancha Dravida primarily because the Brahman communities in this grouping are strict about not eating meat, just like the Brahmans in Rajasthan and Gujarat. The Gurjara Brahman grouping also has Brahman clans from the North Indian group. A case in point being the Goud Gurjara, who are Goud Brahmans that settled down in Gurjara. The example of the Gurjara Brahmans again proves that Gurjara was the name of a province in ancient times, and certainly not the name of an “invading horde” of multiple communities! The map above shows the location of the twin provinces of Maru (Marwar) and Gurjar (Gujarat) as well as the main population centers of the pastoral Gujjars (in green) and those of the Gurjara Brahmans (in pink). Compare these to the map showing the Parihar Rajput settlements around the old bases of the Pratiharas

Indian Historians on the term Gurjara

The early Indian Historians could not escape the established belief of the British rulers that the inhabitants of Western India were “more warlike and less Brahmanical” than the people of the interiors. DR Bhandarkar transcribed the inscriptions in the Gurjara territory along with AMT Jackson and naturally followed the prevailing viewpoint. He went a step further and opined that apart from the Pratiharas, other Rajput clans like the Chauhans and Solankis were also of foreign origin but cited no evidence for this speculation. The nationalist historian RC Majumdar accepted the hypothesis of Gurjara being the name of an invading tribe, and of the Pratihara Rajputs emerging from it, but asserted that the other Rajput clans had an indigenous origin. But in the defense of these Indian historians it must be said that the linguistic data on the pastoral Gujjars was then only being compiled, and the study on language development from Sanskrit to Prakrit to Apabharamsa was still in its infancy. The evidence of language contradicts the foreign tribal origin of the term Gurjara, but there were Indian historians even in that period who opposed this hypothesis on other rational grounds.

As far back as 1925, the historian CV Vaidya lashed out at them: “unaccountable tendency in antiquarians of India to assign foreign and Scythic origin to each and every forward people found in Indian history. Thus the Jats and even the Rajputs are assigned a foreign and a Scythic origin. If the Jats, the Gujars, and the Rajputs with their clearly Aryan features are foreigners and Scythians where are the Indo-Aryans, those people who spoke the Aryan Sanskrit or Vedic language…have they disappeared?” Similarly, Dashratha Sharma, the Rajasthan historian asserted that Gurjara was the name of a province. Another stalwart historian from Gujarat, KM Munshi, emphatically rejected the colonial myths on the term Gurjara: “there is no evidence to prove that the Gurjara Gaur Brahmanas, the Srimala Brahmanas, the Poravada and Osavala Kshatriyas, and the corresponding Vaisyas were of foreign extraction.” The theory of Gurjara being the name of a foreign tribe was contradicted on the lack of references in the historical texts, the many references to Gurjara being a province, the linguistic affinity of Gujari to Rajasthani, and the existence of various communities taking their cognomen Gurjara from the province. The hypothesis now rests entirely on some speculative translations of Pratihara inscriptions.

For instance in the Jodhpur inscriptions, Rohilladdhi and Pellapelli are alternative names used for two Pratihara rulers. These untranslated words could just be colloquial but the colonial historians have taken these to be “proof” of foreign origin…even though these words have not been translated to this day nor have they been linked to any foreign language. In all probability they have a folk origin, as many other untranslated words and phrases in Rajasthani do even today. In the Rajor inscription dated 959 CE, Malthandeva, a feudatory of the Imperial Pratiharas, describes himself as a Pratihara from Gurjara (gurjara-pratiharanvayah) but the colonial historians speculated that this actually means Pratihara clan of the Gurjara tribe. However in most cases the clan is named first and the tribe second (as in Chechi Gujjar). Another line in this inscription refers to “all the neighbouring fields cultivated by (the inhabitants of) Gurjara” (Tathaitat pratyasanna Sri Gurjjara vahita samasta-ksetra sametah) and this is speculated to mean that there was a Gurjara tribe living in that territory engaged in farming. But this contradicts the whole hypothesis that only the warlike elements of the foreign tribe colonized Rajasthan…unless they’re claiming that these mythical Gurjara rulers were also doing farming on the side! The inscription is only talking of the general inhabitants of Gurjara province and not to any tribe, for otherwise Gujjars in more substantial numbers should have been settled here, just as the Parihar Rajputs are.

Oral traditions of the Gujjars

In most places the oral traditions of the Gujjar populace point to a pastoral origin from Rajasthan/Gujarat. A minuscule population of Gujjars settled in Jhalwan, Balochistan, trace their ancestry to Delhi and speak the Sindhi language. In the same province, the Gujjars of the Makran region point to Mewar in Rajasthan as their original home. In NWFP the Gujjars speak Hindko and claim to be descendants of Hindu Rajputs. In Punjab the Gujjars speak a mixture of Gojari and Punjabi and claim a Rajput ancestry…usually by the marriage of a Rajput chief of a particular clan with a Gujjar lady. They too trace their migration into Punjab from the south: Rajasthan or Gujarat. In the Tuzuk-i-Jahangiri the 16th century Mughal ruler Jehangir describes how the district of Gujrat got its name: “I crossed the river by a bridge which had been built there, and my camp was pitched in the neighborhood of the pargana of Gujrat. At the time when His Majesty Akbar went to Kashmir, a fort had been built on that bank of the river. Having brought to this fort a body of Gujars who had passed their time in the neighborhood in thieving and highway robbery, he established them here. As it had become the abode of Gujars, he made it a separate pargana and gave it the name of Gujrat. They call Gujars a caste which does little manual work and subsists on milk and curds.”

There is a substantial Gujjar population in the Indian state of Jammu and Kashmir. The 12th-century Rajatarangini which deals with the history of Kashmir and the neighborhood mentions a number of tribes, like Dards, Khasas, Bhuttas, etc who are still found there, but no mention is made of a Gujjar tribe. This can only mean that they migrated to the western Himalayas in a very late period. The Gujjars in J&K speak the Gojari language and state that their ancestors came from Gujarat…not surprisingly they are mostly vegetarians. From J&K the Gujjars have spread into Himachal Pradesh; first into Chamba and later into Sirmaur, where they are still called Jammuwala Gujjars. In all the places discussed above the Gujjars are Muslims and trace their conversion either to the invasion of Timur in the 14th century or to the reign of Aurangzeb in the 17th century. There is one intriguing point with regard to the Gujjar population in Punjab and the western Himalayas which cements the linguistic evidence of their Rajasthani rather than foreign origins:

- It is significant that the Gujjars living in Punjab trace their connection more with the Rajputs of Rajasthan and not with the local Punjabi tribes. There are for instance no Janjua Gujjars, or Khokkar Gujjars, or Awan Gujjars.

- Similarly Gujjars living in the western Himalayas do not share any connection with the locally prominent Rajput clans. There are no Jamwal Gujjars or Katoch Gujjars.

In western Uttar Pradesh the majority of Gujjars are Hindus. In this region too they trace a pastoral descent and a connection to Rajputs. They had a more warlike reputation than their brethren in the northwest; Gujjar strongholds were noted in the 18th century and Gujjars took part in the region’s uprising against the British in the 19th century. Further south in Central India the minuscule population of Gujjars are primarily pastoral and unwarlike. Here some of the Gujjars claim to have migrated from Gujarat, others claim to have been created by Sri Krishna, and some others by Bhagwan Brahma. They share some clan names with Rajputs while others are called after villages, titles or natural objects.

It is in Rajasthan that the oral traditions of the Gujjars approach anything close to recorded history, even though their population here is less in numbers and restricted to the eastern districts. Here the Gujjars are closely associated with Rajputs and provide nurses for their families. Even in the case of the Jat rulers of Bharatpur, the 1908 Imperial Gazetteer reports: “There are two main endogamous divisions of Gujars, namely Laur and Khari; and in Bharatpur, the former has the privilege of furnishing nurses for the ruling family.” The Charbhujaji Temple in Chittorgarh was constructed in the 15th century by Maharana Mokal, the Sisodia Rajput ruler of Mewar, and it has been managed by the Gujjars living in the neighborhood. Gujjars are further associated with Mewar through the folk deity Devnarayan also known as Deoji.

The legend of Devnarayan: This Deoji was born in the now unknown Bagrawat clan, as an incarnation of Bhagwan Vishnu, and is worshiped by Gujjars, by Kumhars (potters) and Balais (weavers). In Rajasthan, his shrines are at Puvali and Bunjari while in neighboring MP there is a Dev-Narayana temple (built in the 17th century) at Dev-Pipaliya. There is also a temple of his father Sawai Bhoj at Asind in the Bhilwara district. There are different stories about this Bagrawat clan; while all of them agree on the Bagrawats having a Rajput origin on the father’s side, the mother’s community is reported variously. According to a 20th century translation of the Dev Narayan phad rendered by Gujjar Bhopas, the clan originates from a Rajput warrior who slew a tiger (bagh) and married a Brahman woman. The Gujjars are depicted as following the pastoral profession and having been born from a holy cow; in this version, they become associated with the Bagrawats through the marriage of Gujjar women with Bagrawat men. An older version of this legend is given in the 1913 MSS of bardic chronicles: “The word Bagravat means bigra hua, that is, those who have become perverse. They are said to have been descended from the Chauhan Rajputs of Ajmer by their connection with Bania women. The Bagravats were 24 brothers and a sister…They suddenly became very wealthy and spent all their money in wine, women and sensual enjoyments. Bhoj was the most celebrated of the 24 brothers. When a man lavishly spends his money in enjoyments he is compared to Bhoj Bagravat. Bhoj had a son named Deo, commonly called Deoji, who started a new sect called the Bhopas. The Bagravats had a settlement at the village of Harsa near Bilada where their temple and their embankments are still in existence. There is an inscription in the temple dated about 1230 VS.” The version told to Colonel Tod in the 19th century puts the origin of the clan to a Chauhan Rajput father and Gujar mother.

The subsequent tale of the Bagrawats also has different renderings, but to summarize: they are allied with the Chauhan Rajputs of Ajmer and in conflict with the Parihar Rajputs of Ratankot (or Ran or Ran-Binai in other versions). This would date the legend to the 12th century; but Dev Narayan is also associated with the Sesodia Rajputs of Mewar and the founding of Udaipur, which took place more than 400 years later, and is evidently a later addition. The tale of Deoji has similarities to the tales of other folk deities of Rajasthan like Pabuji Rathod who is worshiped by Rabaris or camel herders, and Ramdevji who is worshiped by the leather-working Meghwals. All these tales depict how Rajputs of poor means or mixed origins become associated with the lower castes.

Last rites of the colonial myths

As seen above, the highly speculative colonial hypotheses on the Gurjara province, the Gurjara Brahmans, and the pastoral Gujjars, are a mass of contradictions and are countered by textual references and linguistic evidence. The last remaining piece of the puzzle is the population distribution of the pastoral Gujjar tribe: what alternative hypothesis can explain why they are primarily found outside the ancient territory of Gurjara?

The oral traditions of the Gujjars leave no doubt as to their pastoral origins from Rajasthan. It can be speculated that a severe drought drove them to seek shelter in the relatively fertile eastern Aravalli Hills of Mewar. Here they were called Gujjars because they had migrated from that province, and it is here that their earliest historical memories are found. A pastoral people would primarily be in search of fresh grazing ground for their flocks; the densely forested and riverine tracts of the Gangetic plains do not afford such grazing. But the drier plains of Punjab do and it is here that the Gujjars have migrated in greatest number, absorbing along the way several other communities in their midst, but still preserving at the core a cognate of the Rajasthani language. The turmoil of the medieval Turk invasions would have compelled many to seek shelter in the western Himalayas where they still speak the purest form of this language.

Original Post Credit: HorsesAndSwords Blogspot blog of Airavat Singh