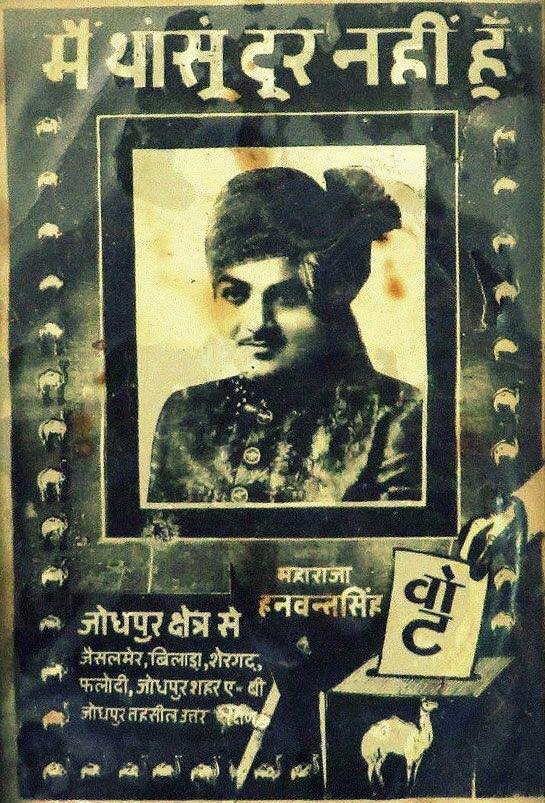

Maharaja Hanuwant Singh Ji

The Maharaja desired Congress Party tickets for half the number of State Legislative Assembly (SLA) seats in his former kingdom but Jai Narain Vyas, the new leader of the Congress in Rajasthan and its interim Chief Minister, offered only a tenth. Vyas, desperate to enlarge his rural base, finally negotiated with the Marwar Kisan Sabha which merged with the Congress on the eve of the elections with, incidentally, an assurance of half the seats contested. And the Rathore was left to go to it alone. It was a battle as impressive as any in his history. “Durbar Bapji”, pleaded Jai Narain Vyas, a little patronizingly, “I beg you. Do not stand for elections. Do not humiliate yourself.” Maharaja Hanwant Singh was unperturbed. “Guruji”, he laughed, “if I were to put a stone up against you, the stone would win.”

The ambitious, and, some would say, audacious former Prime Minister of Marwar, then the interim Chief Minister of Rajasthan, was, in fact, opposing the Maharaja himself in Jodhpur City. It was one of the two SLA seats the popular leader had chosen for, to demonstrate his universal appeal, he had filed his papers to contest elections for a rural seat in the district of Jalore as well. Hanwant Singh, to his credit, tried to the very end to avoid a confrontation with his former Prime Minister whom he held in high regard, even offering him the seat in Jalore uncontested if he withdrew from Jodhpur. Vyas, however, was adamant. “Times have changed Durbar Baapji. Let us rule for you now.” But Hanwant Singh understood his people like no one else. Though not the only Maharaja to contest the Republic of India’s first general elections, he was the only one who had the foresight and courage to form his own party, a union of independent candidates, and accept the challenge.

His candidates for the thirty-five State Assembly and four Parliamentary seats that make up the former state of Marwar were hand-picked, the majority of them Rathores, young, bright and dynamic. His election office was Mehrangarh, not Umaid Bhawan, his symbol the camel and his rallying call Main Thansu Door Nahin, I am not far from you, electrified Marwar as Ran Banka Rathore had never done. “I have no use for privy purses”, he cried at a meeting in the walled city, a mesmerizing orator. “I have you, my people. Raise your hands, my privy purse!” And they did. (Nehru had threatened to revoke the purses if the Princes entered politics).

India’s first General elections were held in January 1952. The result in Marwar was a forgone conclusion but the people were to be denied. At dusk on the twenty-sixth, the day of the counting of votes, Maharaja Hanwant Singh’s two-seater air-plane crashed in southern Marwar as he flew from constituency to constituency for the results. The twenty-nine-year-old Rathore died on the spot. That night, even as they brought his body back to his stunned capital, the results were announced.

In Jodhpur Hanwant Singh had humiliated Jai Narain Vyas. The popular leader barely saved his deposit. (The Rathore polled 62.2 percent of the votes to Vyas’s 17.2 percent) In Jalore too, Vyas had been soundly defeated by an equally embarrassing margin, by the young Champawat Thakur of Bhanswara, Madho Singh. (There the popular leader polled 18.9 percent of the votes.) Dwarka Das Purohit, another prominent member of the Congress Party as well as a former Minister in Marwar’s popular government, had also been defeated convincingly in Jodhpur.

Of the thirty-five assembly seats Hanwant Singh’s candidates had contested, they had emerged victorious in thirty-one. Of the four parliamentary seats contested, they had won all four. The Maharaja had himself won the Jodhpur parliamentary seat, his opponent forfeiting his deposit, while his uncle M.Ajit defeated the veteran Congress leader Gokulbhai Bhatta convincingly in Pali.

Nowhere in India had the Congress been so completely vanquished. Marwar still wanted her Rathores but the Panchranga, suddenly frail and tired, wept at half-mast. “They did not tell me till the next morning. That night they told me that his plane had crashed and that his brothers had gone to bring him back. But I knew. Every time I went towards the window to look at the flag someone would stop me. Then in the morning, I saw Brigadier Zabar in a white safa.” Forty-one years later the pain has not gone away for Jodhpur’s last reigning Maharani.

“Sabotage!” wept Jodhpur and within hours thousands collected around the government buildings baying for the unfortunate Jai Narain Vyas’s blood. The leader, still in shock, had but one place to take refuge, the Umaid Bhawan. And as he rushed to the home of the men he had so long opposed, ashamed, embarrassed and terrified, for the Rathores the humiliation and pain of the Merger seemed suddenly to evaporate in the winter air. The angry crowd, however, followed Vyas to Umaid Bhawan and the palace was soon surrounded. “Send him out!” they demanded as the gates closed and the royal guards armed themselves to protect the Chief Minister of Rajasthan from his people. “He will not leave Umaid Bhawan alive today”, they screamed. Salt was rubbed in Vyas’s wounds that day as the oldest of his adversaries helped him escape to Jaipur.

It was Rao Raja Narpat Singh, personally an admirer of Vyas, though he detested Congressmen, “those bally dhotiwallas”, who had first had Vyas arrested and jailed in 1929, and it was he who escorted him out of Umaid Bhawan, at dusk on 27th January 1952 in the heavily curtained Zenana Cadillac.

In Jaipur, where rioting broke out on the twenty-eighth, Vyas, humiliated beyond measure, announced his retirement from politics but a few months later successfully contested a by-election in the former state of Kishangarh and was elected the Chief Minister of Rajasthan. An early indication of the convoluted path Indian politics was about to take…

(Excerpts from ‘The House of Marwar’ by Dhananjay Singh. Roli Books 1994)