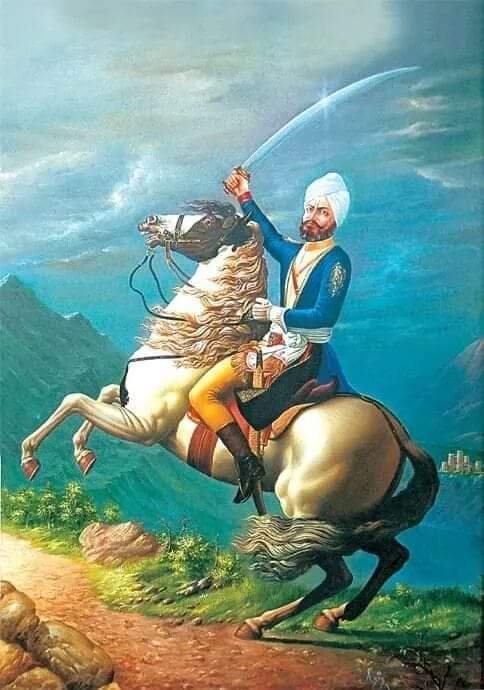

The Tibetans, unable to withstand the Dogra offensive, left the road open through which the Dogra force advanced. They continued their march on December 12, 1841, fell into the ambush. Their rearguard was cut off and could not operate. They were attacked by the Tibetans from all sides. The same day, Zorawar Singh received a bullet in his right shoulder, and as he fell from his horse the Tibetans made a rush. He was, however, not ready to give in at once, and wielded the sword with his left hand. But the Tibetans knew very well that the General was wounded. They made a rush on the Dogra lines, and a Tibetan horseman thrust his lance through his breast, killing him outright. Also, about 40 higher and lower officers of his army and 200 of his soldiers were killed there.

The battle continued for some time but the Dogra troops were soon thrown into disorder, and badly broken on account of the death of their General. They fled in all directions. All the principal officers were captured. One large cannon together with its mount, one large iron cannon, and six flags were captured by the Tibetans, along with numerous muskets, daggers, can-shields and the like. Nono Sodnam, the Ladakhi chief of Zorawar’s army, and others surrendered their arms. and were all imprisoned at Taklakot.

Of the Dogra army, comprising 6,000 including the camp-followers, not more than 1,000 escaped alive; and of the latter, 700 were made prisoners of war. Raja Dhian Singh estimated the number of their troops and followers, who had been lost, a little short of 10,000, about one-third at the hands of the enemy, the remaining by starvation and cold. He said that they also lost much material in the deep snows.

The son of Kahlon Sarkhang escorted the head of the Dogra General to Mang Pao at Lhasa, where, after a close examination, the head was placed at the thoroughfare of Lhasa for the public to view. The Ladakhi chief, Ghulam Khan, and Nono Sodnam, and the Khan of Balti, along with other prisoners, were taken to Lhasa for trial. They were treated variously but on the whole kindly.

The end of Ghulam Khan, who indulged in destroying Buddhist idols and monasteries was, however, pathetic. He was slowly tortured to death with hot irons. Ahmad Shah, the ex-ruler of Skardu and his favorite son, Ali Muhammad, were also among the prisoners. The old man was treated with kindness and was given much honor, but the broken-hearted Khan pined and died in a few months.

Rai Singh, Zorawar Singh’s second in command, was also among the prisoners. For his release Raja Gulab Singh wished the British Governor-General to intercede with the Lhasa authorities. His release, however, could not be affected. The Kahlon of Bazgo and his brother, Nono Sodnam, were considered special friends of the Dogras and were, therefore, treated harshly. Except in the case of a few officers all other prisoners were treated kindly and were sent to Lhasa. After some time most of them became reconciled to their fate, joined the Tibetan service and married Tibetan girls. Some 15 years later, Maharaja Gulab Singh got some of the war prisoners released with the help of the British Government and the Nepalese representative at Lhasa. Only 56 of them returned to Jammu through Nepal, while the remaining preferred to settle in Tibet.

When General Zorawar Singh was killed Dogra troops dispersed in great confusion in various directions. The Tibetans pursued them. The garrison of Taklakot also fled, scarcely realizing that the unrelenting frost would spare no one. The fugitives tried to escape through the mountain range, near the head of the Kali river, into the Indian territory of Kumaon. But in this unopposed flight one-half of them were killed by frost or fell off the heights, and several of them lost their fingers and toes. It was reported that a total of 836 surrendered. Thirteen Dogra chiefs, including Rai Singh, were captured and sent to Lhasa under escort.

Colonel Basti Ram was in charge of the fort and the district of Taklakot in the province of Purang. After the death of Zorawar Singh, the garrison of the fort was completely isolated. Basti Ram bravely continued organizing its defense and probably sought to prolong its occupation till the opportune arrival of some reinforcements. He had made arrangements to keep some sort of communications with the Dogra garrisons at other military posts. He also tried to contact the remnants of Zorawar’s army, but the Tibetan siege of the fort made it impossible for the fugitives to reach its gates.

The Tibetan generals sent out their troops to various points to cut off the Dogra supply lines and communications, and all the Dogra soldiers engaged in transporting supplies were killed.

The Dogras fell short of food, they planned to escape to a place called Chiang Nor. But the Tibetans received fresh reinforcements and a few big guns; they surrounded the fort on all sides, blocking all roads of escape. In a couple of days, they made a strong assault on the fort. The walls gave way at certain points under the heavy gunfire. But the Dogras resisted the attack, and more than 300 perished in the battle. Basti Ram and his surviving companions made good their escape. Chi-Tang fort thus fell to the Tibetans who also seized there over 700 different kinds of weapons. Here the Tibetans also rescued Chei-mei-pa, the Tibetan officer of the Taklakot military post, who was found buried in the ground up to his head.

It is evident that Colonel Basti Ram, the Commander of the Dogra fort of Chi-Tang, held out for several weeks after Zorawar Singh’s death. The garrison at that place did not all at once run away on hearing of Zorawar Singh’s death and the disaster that befell the Dogra army in the battle of Toyo. During this short period of brave resistance, the Dogra garrison seems to have experienced great fluctuations of warfare.

Chi-Tang fort may have fallen to the Tibetans by the first week of January 1842 and Colonel Basti Ram, with 240 sepoys, had escaped by January 9 into the British territory at Askot and had expressed his desire to come to Almora. He probably entered Indian territory by the Lapu Lekh pass. Basti Ram and his companions were rendered all possible help by Mr. Lushington, the Commissioner of Kumaon. Basti Ram also wrote out an account describing what had befallen him and General Zorawar Singh, and the same was forwarded to Raja Gulab Singh by Mr. Lushington on January 16, 1842. Later, Basti Ram and 127 of his followers were permitted to leave for Jammu in July, whereas 40 men who were unable to move were left at Almora.

Comments

The one great cause of the Dogra defeat was the extreme cold and deep snow. “The Indian soldiers of Zorawar Singh,” writes Alexander Cunningham, “fought under very great disadvantages. The battlefield was upwards of 15,000 feet above the sea, and the time was mid-winter when even the day temperature never rises above the freezing point, and the intense cold of the night can only be borne by people well covered with sheep-skins and surrounded by fires.

The breakdown of Zorawar’s commissariat also adversely affected his war potential. The barren and sparsely populated plains of western Tibet could not keep up the efficiency of even a few thousand Dogra sepoys. When winter blocked all the passes, the invaders found it difficult to procure adequate supplies from the country around or from Ladakh.

Another cause seems to have been that many of the Baltis and Ladakhis and the local Hunias deserted the Dogras and joined the Tibetans. This must-have undermined Zorawar’s war strategy at the eleventh hour. The diplomatic treachery can also not be ruled out. The British pressure for the evacuation of the conquered areas and efforts at mediation seems to have put Zorawar Singh off his guard. On the eve of the Tibe¬ tan advance on Taklakot, he had actually recalled his advance posts stationed to block all passes and by-passes through which the Tibetan armies could cross down to the Manasaro- var lake region. In the absence of advance posts, Zorawar Singh received no timely news of the massing of the Tibetan troops on the west of the Mayum pass. When he received the information it was too late.

Zorawar Singh appears to have fallen a victim of his own miscalculation and to the British calculated interference in the affair. He miscalculated that the Tibetans would not be able to mobilize against him during the winter because of the blocking of Mayum and other known passes due to snow¬ fall, He, therefore, withdrew most of his forces to his Tirath- puri wintering camp.

Zorawar Singh possibly made the same miscalculation the Napoleon & Hitler did before & after him. The invisible cause of defeat, which vanquishes great conquering armies even when these have all the forces of their power intact, cannot be ruled out. Often the layout of a country and the effects of its extreme climate become a potent factor in the defeat of an army and all provisions made against such eventualities fail to change the course of events.

In Tibet, he had to fight two enemies, the second being the elements of nature—altitude, climate, and terrain. In a way, Zorawar Singh lost the battle not so much to the Tibetans as to the rigours of the Tibetan winter.

“It was a great mistake,” says A. H. Francke, “on the part of Zorawar to start on this new expedition at the approach of winter.” In this case, it was miscalculation to lead an Indian army in winter in the battlefield which was situated at the altitude of 4,570 meters and he committed the same blunder by invading Tibet in winter which was previously made by Mirza Haider, the Turco-Mongol military general, ruler of Kashmir in 1500s and therefore met with a similar, rather worse, disaster.

Nevertheless, his exploits brought honor not only to him personally but to the entire military system of India. The usual belief that the Indian armies remained confined to their own soil and never won laurels in foreign countries, have been belied by the Dogras more than once, and it shows that Indian forces in the past also could conquer foreign lands if they so choose.

The Indian soldiers of Nurpur-Pathankot Raj extended Mughal conquests beyond the Hindu Kush while the Dogra force under Zorawar extended the Indian frontier beyond the highest northern mountains. These are no mean achievements of the martial spirit of India which is usually wedded to the ideal of peaceful coexistence with its neighbors from times immemorial, although her neighbors have frequently violated her borders and desecrated her soil by unnecessary bloodshed.

He was extremely cautious in his movements, so essentially necessary considering the naturally protected position of western Tibet and his entire want of the knowledge of the geographical conditions of this country. But, as he had a keen eye for the defects of his enemy, and was a great strategist, all these difficulties were overcome.” He proved himself a true soldier in the endurance of extraordinary hardships. He was a great military leader, an undaunted soldier, and a master strategist. He had carried his Tibetan campaigns to a point where the frontiers of Nepal and Kumaon met the eastern-most fringe of his conquests. He carried the boundaries of the Jammu Raj to the heart of Tibet, to verge on the western part of Nepal whose ruler sent his representatives to welcome the Dogra conqueror at Tirathpuri.

His crossing of the Zanskar range in the middle of the winter in 1835 to surprise the Ladakhis and his spirited offensive orders in the battle of Manasarovar turned the defeat into victory. The mere fact that a person born and brought up in the warm climate dared to conquer Ladakh, Baltistan, and Tibet proves his great martial spirit.

He led a very simple life, lived on his meager pay and never made money from his campaigns or accepted any bribe or presents. He deposited each and every pie obtained during his campaigns in the State treasury. He never sent any dispatches or information about his conquests except the revenue and tributes, and Gulab Singh had to discover from others what new country his General had conquered. He was so honest that once when Gulab Singh asked him to demand something for himself he demanded only two things: food to eat and the clothes used by Gulab Singh himself to wear and nothing else. He never accepted gifts nor allowed his soldiers to accept them. Looting and pillaging were unknown to his soldiers, for his punishments were exemplary.

Zorawar Singh’s victories had produced an awful impression on the Tibetan people. They took him to be a superman. It is said that when he died his blood and flesh were distributed by the Tibetans among themselves to be kept as sacred souvenirs. His head was severed and taken to Lhasa for enshrining in a Chorten (A Tibetian name for a Stupa - a mound-like or hemispherical structure containing relics that is used as a place of meditation.). It is said that the Buddhists of Tibet still pay their respects to these sacred relics in the belief that it would avert the wrath of the spirit of the Dogra General and prevent it from entering the body of another man to wreak vengeance on the Tibetans. The Tibetans are said to have built a large Chorten on the battlefield of Toyo where Zorawar was killed in order to forestall the possibility of his reincarnation into another human form for the destruction of Lhasa.

For, his heroic fight against tremendous odds won him the admiration and esteem of his opponents to this extent that they kept pieces of his flesh in their homes under the impression that possession of the flesh of such a gallant soldier would confer a bold heart on them. They also raised a big Chorten over his bones—an honor they reserved for their high priests only. Pieces of his mortal remains were placed in certain monasteries also.

His capture of the famous ‘Mantalai’ (i.e. Manasarovar) flag, which is now the proud possession of 4th Battalion of the JAK Rifles. The flag was captured during an action fought on August 7, 1841, at Dogpacha, near Missar, a place about one day’s march from Tirathpuri in the district of the famous Manasarovar and Rakastal lakes.

Zorawar stands out as a leader of men, particularly under trying and difficult conditions which distinguish him as a military general from most of the others. He always believed in personal example and was often found amongst the leading troops in the battle. In fact, he was always present wherever his personal presence was required. He would have defeated the Tibetan troops and occupied Lhasa before the winter. However, it was not to be. After having been deflected from his main aim by a strange hand of destiny cast through the British diplomacy, Zorawar was content with his achievements and went for a pilgrimage to various religious monasteries, the sacred Manasarovar Lake and Mount Kailas. He decided to withdraw to Leh after stationing garrisons at important places and forts. But his death on December 12, 1841, upset the apple cart of his Tibetan campaigns turning the Tibetan expedition into a complete disaster.

The human machinery with whose medium Zorawar got such great victories, was organized on such sound, lines which gave it unity and strength and developed its confidence, optimism, and high morale. Good administration seems to be Zorawar’s strongest point. He knew that high altitude warfare in cold regions required acclimatization, hard training, and proper administration. The first he achieved in Kishtwar where his troops got training for many years at a height of more than 1,830 meters before they entered a career of conquests in Ladakh and Baltistan.

General Zorawar Singh had no son to perpetuate his line. He had three wives. The first one was from the Langeh Rajput house of Ambgarohta village in Jammu, who died at an early age. The second and third wives were real sisters belonging to a Rajput family of Gai village near Pauni-Pahrakh. Their names were Asha Devi and Lajwanti, the latter being the elder of the two. Asha Devi accompanied the General on his Tibetan expedition and had performed pilgrimage to the Kailas and the Manasarovar lake in the company of her husband. When the General decided to give battle to the Tibetans, he sent Asha Devi back to Leh under military escort, from where she returned to Riasi under the protection of the Dogra officers.

As the mountain passes were blocked by snow, the news of the death of Zorawar Singh reached Riasi a month and a half later. On the receipt of this sad news, the two wives of the General prepared for the Sati rite. Gulab Singh sent his eldest son, Udham Singh to prevail on them to refrain from this act. The elder, Lajwanti, thus changed her mind, but the younger, Asha Devi, unable to withstand the pangs of separation, could not refrain from the act. Holding in her lap the turban of her husband she immolated herself on the banks of the Chenab which flows under Bijaipur, the residence of General Zorawar Singh. The funeral pyre was lit by Thakur Dharam Singh, lifelong faithful companion of the General, whom she blessed with a boon. A Samadhi was built at the spot where she performed Sati, but the same has now been washed away by high floods in the river.

Thus ended the saga of one of the bravest Rajput, a son of the soil.